Since 2008, the term “land grabbing” gained notoriety around the globe. It refers to large-scale land acquisitions mainly by private investors but also by public investors and agribusiness that buy farmland or lease it on a long-term basis to produce agricultural commodities. These international investors, as well as the public, semi-public or private sellers, often operate in legal grey areas and in a no man’s land between traditional land rights and modern forms of property. In many cases of land grabbing, one could speak of a land reform from above, or of the establishment of new colonial relationships imposed by the private sector.

The IAASTD covers the problem of unfair distribution of land, which has existed for many centuries, as well as approaches to agrarian reforms and communal land use. Its key message is simple: Secure land tenure, property rights and other forms of common ownership, including access to water, are an essential prerequisite for family farms to invest in their own future. They provide the basis for all forms of sustainable development and land cultivation. There is hardly any other economic sector with so little transparency as in the area of land ownership. Even in times of Google Maps, a global land register is still a long way off. History often plays a key role: Past social and economic systems, ideologies, tribal rights and gender privileges, as well as scars of war and displacement, remain visible. The power over land registers is still today not granted by courts in all parts of the world but often seized violently by both private and public actors.

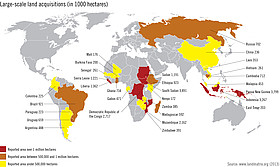

Gobal land rush in countries with weak governance

Since 2009, the Land Matrix, a joint independent land-monitoring initiative of civil society, intergovernmental organizations and research institutes, has collected key information regarding land grabbing. For example, it shows that almost nine percent of Africa’s total area of arable land has changed owners since 2000. The largest land acquisitions are concentrated in countries with weak governance structures. In these countries, the proportion of hunger and malnutrition in the population is also very high, for example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Mozambique, Ethiopia and Sierra Leone.

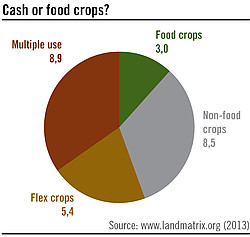

Only 9% of the agricultural projects listed by the Land Matrix are exclusively destined for food production. The more common objective of land acquisition is the cultivation of biofuels or energy crops for export, fibers, animal feed or traditional cash crops such as coffee, tea and tobacco. A large proportion of land is used to cultivate so-called “flex crops”, which can be used either for food or other purposes, particularly for biofuels.

Large-scale land acquisitions mainly target readily accessible, fertile land, in densely populated areas, cultivated by small-scale farmers. In many cases of land grabbing, securing access to water also plays an important role. Those affected by these land deals commonly receive insufficient compensation and are not consulted or involved in the process. It is also worth noting that large parts of the land acquired are often not used immediately and that the rate of abandoned projects is quite high. The Land Matrix, therefore, differentiates between concluded, intended and failed deals.

Can voluntary guidelines help?

In May 2012, the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) of the United Nations officially endorsed the “Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security”. They are intended to provide governments, investors and civil society with rules on how to protect, document and administer legitimate rights; how to organize a change of land ownership; how to define public priorities and goals for land use; and how to deal with conflicts. The guidelines define access to land in the context of human rights, demanding gender equality and transparency, the rule of law, respect for different tenure systems and values, early consultation of all people who are likely to be affected and peaceful conflict resolution, as well as both public and private responsibility for sustainability, food production and employment. Most paragraphs start with the words “States should”.

The guidelines are a collection of democratic conditions founded on the rule of law, something that is often not prevailing in the countries ranking high on the list of popular land grabbing destinations. In practice, this collection of principles, suggestions and intentions are only likely to become relevant if the governments that promote or tolerate land grabbing in their countries face consequences if they are not observed, for example, loss of development aid or the suspension of cooperation agreements. They could also become an effective tool if companies that violate the guidelines become subject to sanctions imposed by trading partners, but also by the companies’ countries of origin. Four years after the adoption of the guidelines, examples of such an effective implementation are still missing.

Trade in agricultural commodities creates a global land market

There are several reasons behind the growing interest of international investors in large-scale land deals. Firstly, there is an expanding market for agricultural commodities that can be traded globally and are thus not dependent on the purchasing power of local populations. Secondly, the increasing scarcity of fertile soil is a trend that has not gone unnoticed by investors. Thirdly, most analysts agree that although food prices have once again decreased following the spikes in 2007-2008 and 2010-2011, they will remain above pre-2007 levels. The effects of climate change and weather shocks may increase the level and volatility of food prices. For capital investors in search of investment possibilities, arable land, therefore, is an attractive choice due to a predicted future value increase, even in areas where yields are not ideal in the short term. In Europe, large-scale land acquisitions in countries such as the Ukraine and Romania are considered safe business. This frequently leads to the displacement of family farmers and drives up prices for farmland, making it hard for small-scale and young farmers to obtain land.

Facts & Figures

Only 9% of the agricultural projects listed by the Land Matrix in November 2018 (total area 40.98 million hectares) were exclusively destined for food production. 38% of the area was intended for non-food crops and 15% for the cultivation of flex-crops that can be used for biofuels and animal feed, as well as food. The remaining land was intended for the cultivation of different crops at the same time.

Since the year 2000, foreign investors have acquired 26.7 million hectares of land around the globe for agriculture, according to a Land Matrix report that covers 1,004 concluded agricultural deals. Africa accounts for 42% of the deals, and 10 million hectares of land. Land acquisitions are concentrated along important rivers such as the Niger and the Senegal rivers, and in East Africa.

- Analytical Report of the Land Matrix II: International Land Deals for Agriculture. Land Matrix, 2016

For the decade spanning 2007-2017, GRAIN has documented at least 135 farmland deals intended for food crop production that backfired. They represent a massive 17.5 million hectares, almost the size of Uruguay. These are not failed land grabs, since the land almost never goes back to the communities, but failed agribusiness projects. Failed land grabs for agricultural production peaked in 2010, but they are on the rise again since 2015.

Despite a history of customary use and ownership of over 50% of the world’s land area, indigenous peoples and local communities – up to 2.5 billion women and men – possess ownership rights to just one-fifth of the land that is rightfully theirs. The remaining five billion hectares remain unprotected and vulnerable to land grabs from more powerful entities like governments and corporations.

Of the 10.3 million farms in the EU, two thirds (65.4%) are less than 5 hectares in size. In 2016, they worked just 6.1% of the EU’s utilized agricultural area. In contrast, large farms (100 hectares and above), representing just 3.3% of the total number of farms, controlled half (52.2%) of all farmed land. The 7% of farms that were of 50 hectares or more in size worked a little over two-thirds (68.1%) of the EU’s utilized agricultural area.

Land ownership in Europe has become highly unequal, in some countries reaching proportions similar to Brazil, Colombia and the Philippines – all notorious for their unequal distribution of land and land-based wealth.

Land investors appear to be targeting countries with poor governance in order to maximize profit and minimize red tape. Analysis by Oxfam shows that over three-quarters of the 56 countries where land deals were agreed between 2000 and 2011 scored below average on four World Bank governance indicators: Voice and Accountability, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law and Control of Corruption.

A study of the economic impact of land grabbing on rural livelihoods estimates that the total income loss for local communities is $34 billion worldwide, a number comparable to the $35 billion loaned by the World Bank for development and aid in 2012. The study looked at the 28 countries most targeted by large-scale land acquisitions and used data from the Land Matrix database.

Behind the current scramble for land is a worldwide struggle for control over access to water. In recent years, Saudi Arabian companies have acquired millions of hectares of land overseas to produce food to ship back home. The country does not lack land for food production; what’s missing is water for irrigation.