Even today, agriculture is an important source of income and the world’s largest business. One-third of the economically active population obtains its livelihood from agriculture. In Asia and Africa, millions of small-scale and subsistence farmers, pastoralists, fishermen and indigenous peoples produce most of the food consumed worldwide, in most cases on very small plots of land. Over the past decades, agricultural policy and international institutions, as well as private and public agricultural research have often considered small-scale and subsistence farmers as backward “phase-out models” of a pre-industrial form of production. For more than 50 years, “grow or die” has been both the capitalist and socialist principle for progress, with just a few exceptions. The widely held belief was that only large economic units were capable of achieving increases in productivity on a competitive basis through modern and rationalized cultivation methods, mainly with chemical inputs and the use of machinery. A global increase in productivity was considered necessary to feed a rapidly growing world population.

The agricultural treadmill

The IAASTD describes this development model of industrialized nations as the “agricultural treadmill”. It is based on technological advances achieved through mechanization, plant breeding for high-yielding varieties, the use of agrochemicals and genetic engineering, etc. With increasing external inputs, the unit costs of production are declining and the productivity per worker is increasing. Production is growing and producer prices are falling. The only businesses that can survive on the market are those that remain one step ahead of their competitors by investing in rationalization and expansion, or those with locational advantages. If others catch up with them, another round begins. An end to this treadmill is not in sight: The more global the market, the higher the speed and the more incalculable the game becomes for each participant.

The IAASTD calls into question the idea that this universal principle of technological progress in a free-market economy is the ideal concept for sustainable food production and the organisation of agriculture. Firstly, fertile soils – the most important basis of agriculture and a resource that can rarely be multiplied – are seldom distributed fairly. Almost nowhere in the world does access to land follow classical market rules of supply and demand. The distribution of soils is shaped by the historical legacy of feudalism, colonialism and patriarchal inheritance rights and has always been the result of very particular machinations and struggles for power, which are rarely transparent, fair and non-violent.

Secondly, agriculture in many regions of the world depends on massive public interventions and subsidies which frequently pursue short-term macroeconomic goals, such as low food prices, as well as geostrategic interests. The capability of a country to supply its own population with food in the case of war and conflict, but also the threat to stop food exports, still belong to the classical arsenal of power politics of states.

Subsidies for certain agricultural commodities, producers, forms of production and exports are mainly paid in industrialised countries. It is predominantly large agricultural enterprises and big trade and processing companies that profit from these subsidies. Worldwide, direct and indirect subsidies have a profound influence on production costs and prices of agricultural commodities.

The end of industrial productivism

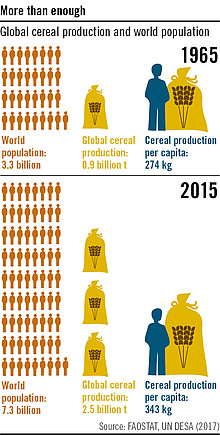

In general, the large-scale industrialisation of agriculture in North and South America, Australia and Europe and the “Green Revolution” in Asia have led to impressive successes in increasing productivity and rationalisation over the past fifty years. The increase in global agricultural production has outstripped population growth. According to different estimates, our current agricultural production could feed 10 to 14 billion people if it was used exclusively and as efficiently as possible as food.

However, the one-sided focus on productivity of industrial agriculture exploits the available natural resources of our planet to an untenable and unsustainable extent. The basic strategy to replace human labour with farm machinery, agrochemicals and fossil energy, is a dead end in times of climate change, dwindling oil reserves and overexploited natural resources. We have exaggerated the problem with the concept of producing huge amounts of meat and agricultural commodities in highly rationalised monocultures and from just a few standardised high-yielding crop varieties which then are processed into the apparent product variety we are used to seeing in our supermarkets. Industrial agriculture consumes large amounts of pesticides, mineral fertilisers, energy and freshwater resources, and produces large volumes of greenhouse gas emissions. Depleted and salt-affected soils, deforestation and the contamination of entire watercourses, as well as an unprecedented loss of biodiversity are the ecological costs of these advances.

The IAASTD clearly debunks the myth that industrial agriculture is superior to small-scale farming in economic, social and ecological terms. The report argues for a new paradigm for agriculture in the 21st century, which recognises the pivotal role that small-scale farmers play in feeding the world population. Small-scale, labour-intensive structures that focus on diversity can guarantee a form of food supply that is socially, economically and environmentally sustainable and that is based on resilient cultivation and distribution systems.

However, the IAASTD is far from romanticising the current form of small-scale and traditional agriculture, or calling for a return to pre-industrial conditions. It offers a clear and detailed description of the problems small-scale farmers frequently face in terms of productivity and efficiency, as well as the practices they use which are hazardous to human health and the environment. Both loss of traditional knowledge and lack of up-to-date knowledge are contributing to the misery of many smallholder families and subsistence farmers. Many traditional methods of production no longer offer a sustainable perspective. The challenges of the future can only be met with enormous boosts in innovation and with qualified farmers.

Food efficiency instead of increased surplus value

For this reason, the IAASTD considers investment in smallholder production the most urgent, and a secure and promising means of combating hunger and malnutrition, while at the same time minimising the ecological impact of agriculture practices. Improved methods of cultivation, mostly simple technologies and basic knowledge, more adequate seeds and a large number of agroecological strategies all provide huge potential for boosting productivity in a sustainable way. They are more likely to make sure that the additional amounts of food produced are actually available where they are needed most.

If small-scale farmers have sufficient access to land, water, credit and equipment, the productivity per hectare and per unit of energy use is much higher than in large intensive farming systems. In general, smallholder production requires considerably fewer external inputs and causes minor damages to the environment. Small farms are more flexible and better at adapting to local surrounding and changing conditions. As small-scale farming is more labour-intensive, it also enables more people in the countryside to make a living.

Preconditions for this are a minimum of legal certainty, sufficient income and an infrastructure that is tailored to their needs: wells, streets, public health care, access to education and agricultural extension, as well as means of communication. Also in areas where small-scale farmers could produce more, this often does not happen due to a lack of basic storage and transport facilities, as well as access to local and regional markets that would make such efforts rewarding. Fair credit conditions for basic investment and insurances when crops fail could contribute towards making their risks more manageable. However, public investment in rural development in many developing countries, especially Africa and the least industrialised regions of Asia, has been severely neglected over the past 30 years. Private investment has been made in just a few export-oriented areas, which are often also the focus of national and international support programmes. The IAASTD describes this as a fatal global trend towards a decapitalisation of small-scale farmers, which must be urgently reversed.

“Grow or die” is no longer modern

The IAASTD made the case for supporting small-scale farmers, questioning for the first time the agricultural paradigm “grow or die” of past decades. In recent years, many national and international development organisations and agencies have taken up this plea to invest in smallholders, at least in their publications and declarations of intent. The United Nations even declared 2014 the International Year of Family Farming. In practice, however, small-scale farmers are “difficult customers” for global players: Efforts and expenses are higher for investing in smaller units of production. It does not always prove effective to delegate the administration of programmes and funds to national or regional authorities since the disregard for small-scale farmers is often deeply rooted, especially in the cities.

Ministries of agriculture in the European Union and other industrialised countries also seem to consider the IAASTD’s message as purely related to development policy. According to their reading, small-scale farming structures may be an effective means for fighting hunger in the poor countries of the Global South. The modern, “knowledge-based bio-economies” of industrial nations, on the other hand, requires the continued “structural adjustment”.

Facts & Figures

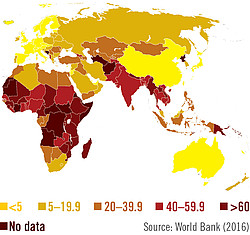

Approximately 3.4 billion people – or 45% of the world’s population – live in rural areas. Roughly 2 billion people (26.7% of the world population) derive their livelihoods from agriculture. In 2016, an estimated 57% of people in Africa were living in rural areas. 53% of the population was economically active in agriculture.

Agriculture employed some 873 million people in 2021, or 27% of the global workforce, compared with 1,027 million or 40% in 2000. In Asia, agricultural employment has declined from 787 million to 581 million people, meaning that more than one out of every four agricultural workers has left the sector for another job outside agriculture since 2000. In Europe, agricultural employment decreased by 49% from 34.4 million in 2000 to 17.5 million people in 2021. During the same period, agricultural employment in Africa increased from 164 million to 229 million people in 2021.

In 2017, an estimated 866 million people were officially employed in the agricultural sector: Of these, 292.2 million were located in Southern Asia, 148.4 million in Eastern Asia and 215.7 million in sub-Saharan Africa. The agricultural sector accounted for 57.4% of total employment in sub-Saharan Africa and 42.2% in Southern Asia. Although the share of total employment in agriculture has declined over the past decade, the total number of workers in agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa has grown.

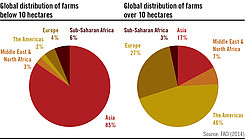

The vast majority of the world’s farms are small or very small. Worldwide, farms of less than 1 hectare account for 72% of all farms, but control only 8% of all agricultural land. Farms between 1 and 2 hectares account for 12% of all farms and control 4% of the land. In contrast, only 1% of all farms in the world are larger than 50 hectares, but they control 65% of the world’s agricultural land.

There are more than 570 million farms in the world. More than 90% of farms are run by an individual or a family and rely primarily on family labour. Family farms occupy a large share of the world’s agricultural land and produce about 80% of the world’s food.

Of the 10.3 million farms in the EU, two thirds (65.4%) are less than 5 hectares in size. In 2016, they worked just 6.1% of the EU’s utilized agricultural area. In contrast, large farms (100 hectares and above), representing just 3.3% of the total number of farms, controlled half (52.2%) of all farmed land. The 7% of farms that were of 50 hectares or more in size worked a little over two-thirds (68.1%) of the EU’s utilized agricultural area.

In the financial year 2016, around 1.8% of the beneficiaries of EU direct payments granted to 6.7 million farms received €50,000 or more, representing around 31% of the total amount of direct payments (41 billion euros). Around 93% of the beneficiaries received €20,000 or less but this large group only received 42% of the total amount of direct payments.

Smallholders can be highly productive. In Brazil, family farmers on average provide 40% of the production of a selection of major crops working on less than 25% of the land. In the United States, family farmers produce 84% of all produce – totalling US$ 230 billion in sales, working on 78% of all farmland. Family farmers in Fiji provide 84% of yam, rice, manioc, maize and bean production working on only 47.4% of the land.

“The world needs a paradigm shift in agricultural development: from a ‘green revolution’ to an ‘ecological intensification’ approach. This implies a rapid and significant shift from conventional, monoculture-based and high-external-input-dependent industrial production towards mosaics of sustainable, regenerative production systems that also considerably improve the productivity of small-scale farmers.”

A study comparing yields of organic and conventional farming from over 366 studies and trials found that organic farming yields equate to 75% of the average yield from conventional farming production. It was noted that yields depend on many conditions, with organic farming achieving 95% of conventional yields when applied with good management practices, focusing particular on crop types and soils. The study did not consider efficiency or the environmental costs associated with conventional production, which include CO2 emissions or soil erosion.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that the total support from taxpayers and consumers arising from policy measures that support agriculture in OECD countries stood at almost USD 315.5 billion in 2017. Support to farmers across the OECD area as measured by the Producer Support Estimate (PSE) amounted to USD 228 billion.

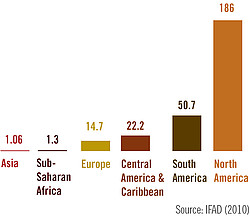

In the United States, the mean farm size is 178.4 hectares. In Latin America it is 111.7 hectares. In sub-Saharan Africa however the average size amounts to just 2.4 hectares. In Asia this figure is lower still: 1.8 hectares in South East Asia and 1.4 hectares in South Asia.