Although the IAASTD firmly warns us against hoping for any kind of ‘silver bullet’ solutions, it leaves no doubt that respecting the basic rights of women, especially in rural areas in Asia and Africa, is by far the most effective means of fighting hunger and poverty in a sustainable way. This ranges from the fundamental right to bodily integrity, to the freedom to choose whether to marry and if/when to have children. Whether women can exercise their right to learn to read and write, to own land, to have access to water, livestock and machinery; or whether they are allowed to open a personal bank account or take a loan can be a decisive factor in women’s chances of being able to provide for themselves and their families. If women have the opportunity to self-organise and take part in decision-making, often the whole community will benefit.

Gender equality – the best solution for hunger

Compared to men, women and girls are still more severely affected by poverty, hunger and disease. When food is scarce, female family members often get the smallest portions. On the labour market, women are literally paid starvation wages. Mothers also suffer most from lack of medical care and balanced diets. The responsibility for the survival of their children commonly demands additional sacrifices from them. In Africa and large parts of Asia, women in rural areas bear the main responsibility for taking care of children and elderly. They also constitute the majority of the agricultural labour force in small-scale and subsistence farming. Since official statistics do not capture unpaid work, be it in the garden, in the field or in the household, they insufficiently represent women’s actual share in agricultural work. Women in Africa and Asia who live in rural areas are often doubly affected by discrimination.

The feminisation of agriculture

The number of female-headed households is increasing as a result of civil wars, AIDS and the migration of men to cities in search of paid work. The IAASTD describes this as ‘the feminisation of agriculture’ that is having profound and far-reaching effects, both positive and negative. Offering qualification opportunities, extension services and agricultural training to women therefore needs to be a priority of future development policies. Initially, the number of women in agricultural extension and research needs to be increased.

The industrialisation of agriculture falls mainly within typically male areas of decision-making, including the economic risks involved. These areas include the competitive use of machinery, agrochemicals and high-breeding plant varieties; the cultivation of cash crops and the breeding of large livestock for supra-regional markets. Men’s involvement in these often risky activities have in the past decades brought about ruin for many farmers, forcing them to migrate to the slums of the cities and causing many to commit suicide out of desperation. Women in contrast tend to be more cooperative and cautious, and try to minimise risks in food production, processing and supply, and they opt for social self-help and preventive health care. Men’s forms of farming practice geared toward national and international markets therefore often undermine female domains and competences. Women frequently provide their families with food, from diversified cultivation of vegetables, fruits, tubers and herbs in their gardens, as well as from the rearing of small livestock.

Female innovation

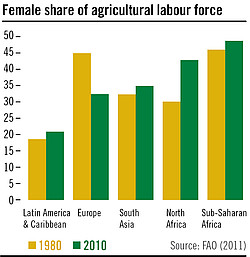

These kind of simplistic characterisations do no justice to the complex gender relationships that differ according to region, history and culture. However, they show some basic lines of future development, in which the IAASTD recognises maybe the biggest potential for innovation in order to achieve its goals of sustainability and development. The chances of escaping hunger and misery disproportionately increase if women become empowered in small-scale agriculture and regional development systems oriented primarily towards local markets and supply, and where agricultural production of export and non-food crops is only a secondary possibility to achieve additional income. The FAO estimates that women comprise, on average, 43% of the agricultural labour force in developing countries. If they had equal access to productive resources, they could increase yields on their farms by 20 to 30%.

Worldwide, women are impressively demonstrating that they are willing and able to use their qualifications and growing self-determination in order to directly increase social prosperity and to preserve natural resources. The clear message of the IAASTD that women can make the decisive difference was not a new insight back in 2008. However, in contrast to other messages, it fell on fertile ground. The World Bank, the FAO and public and private development organisations, but also a growing number of governments and institutions, have today taken up the issue of gender mainstreaming in all of their programmes and activities. Even though successes in this area are being obtained at a snail’s pace, they can be observed in many regions of the world.

Facts & Figures

The rush to invest in farmland in Africa is having an immediate impact on women’s land-use options, on their livelihoods, on food availability and the cost of living, and, ultimately, on women’s access to land for food production. Women’s knowledge, their socio-cultural relationship with the land, and their stewardship of nature are also under threat.

In low-income countries, 46 million children suffer from stunting. If all women completed primary education, 1.7 million fewer children would be in this situation. If all women had access to a secondary education, 11.9 million children would be saved from stunting, equivalent to a decrease of 26%.

The reduced agricultural productivity of women due to gender-based inequalities in access to and control of productive and financial resources costs Malawi USD 100 million, Tanzania USD 105 million and Uganda USD 67 million every year. Closing the gender gap could lift as many as 238,000 people out of poverty in Malawi, 119,000 people in Uganda, and 80,000 people in Tanzania each year.

In developing countries in Africa, Asia and the Pacific, women typically work 12 to 13 hours per week more than men; yet, women’s contributions are often ‘invisible’ and unpaid.

Rural women carry a great part of the burden of providing water and fuel. In rural areas of Malawi, for example, women spend more than eight-fold the amount of time fetching wood and water per week than men. Collectively, women from Sub-Saharan Africa spend about 40 billion hours a year collecting water.

In the 97 countries assessed by the FAO, female farmers only received 5% of all agricultural extension services. Worldwide, only 15% of those providing these services are women. Just 10% of total aid provided for agriculture, forestry and fishing goes to women.

On average, women comprise 43% of the agricultural labour force in developing countries, ranging from 20% in Latin America to 50% in Eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. If they had the same access to productive resources as men, they could increase yields on their farms by 20–30%.

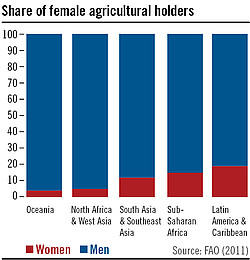

Due to legal and cultural constraints in land inheritance, ownership and use, less than 20% of land-holders are women. In North Africa and West Asia, women represent fewer than 5% of all agricultural landowners; while across Sub-Saharan Africa, they make up 15%. This average masks wide variations between countries, from under 5% in Mali to over 30% in Botswana. Latin America has the highest share of female agricultural holders, which exceeds 25% in Chile, Ecuador and Panama.

Women are of vital importance to rural economies. Rearing poultry and small livestock and growing food crops, they are responsible for some 60% to 80% of food production in developing countries.

In many farming communities, women are the main custodians of knowledge on crop varieties. In some regions of sub-Saharan Africa, women may cultivate as many as 120 different plants alongside the cash crops that are managed by men.