Throughout the past decade, many governments regarded the replacement of petroleum with renewable resources as a “green” and “silver bullet” solution for reducing our dependence on fossil fuel energy and cutting greenhouse gas emissions. It was also hoped that renewable resources would open up new markets for agriculture. The IAASTD was one of the first reports to warn against this way of thinking. Today, almost all international institutions harbour serious doubts regarding agrofuel production, primarily due to its impact on food prices and the competition it creates for arable land and water resources. Even the positive climate effects of biofuels have become highly contested.

Public blending targets and subsidy measures for the production of fuel from maize, rapeseed and other crops have resulted in a significant boom in the cultivation of renewable resources, both in the EU and the US. For Brazil, Malaysia and Indonesia, sugar cane and palm oil for agrofuel production have become important export goods. Soybean oil is increasingly being used as a feedstock for biodiesel production. Africa’s unexploited agricultural land is often considered the “promised land” for the production of renewable fuels. Since the explosion of global food prices in 2008, in which the biofuels boom played a substantial role, worldwide disillusionment has set in. In 2011, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the FAO and other UN organisations made an appeal to the G20 countries, in particular the US and the EU, to remove all provisions and national policies that subsidise or mandate biofuel production and consumption. Instead, they recommended seeking alternatives to reduce carbon emissions and focus on energy efficiency, including for agriculture itself. However, due to diverging interests, the heads of state of the G20 countries failed to agree on a common line in the “food or fuel” debate.

The investment-intensive agro-energy boom has generated high profits for several large companies and further aided the concentration process among US and European farmers. The price increases for cereals, sugar and oilseeds in recent years, to which this new and almost insatiable demand for agro-energy has contributed, are of course felt by all farmers and consumers on the market. In view of a massive biofuel lobby, neither the EU nor the US has yet taken convincing steps to counteract the trend. However, bills are now on the table on both sides of the Atlantic with the aim of slightly reducing the once enormous targets for biofuels and agro-energy. In the US, where 40% of the maize harvest and 23% of soybean oil are converted into ethanol and biodiesel respectively, the heavy subsidies have been questioned due to austerity measures and because fracking is tapping new gas and oil reserves. The EU approved a 7% cap on first-generation crop-based biofuels that can be counted toward the EU’s 2020 renewable transport energy target.

The IAASTD notes that the frequently quoted positive climate effects of biofuels are controversial. When biofuels are burnt, only as much CO2 as was previously absorbed by the plant is released into the atmosphere. However, the cultivation of the crops and their processing into fuel requires intensive energy input. Enormous CO2 emissions occur if forests are cleared to generate new land, either directly for the cultivation of energy crops or indirectly to replace land for food crops that was converted to biofuels production elsewhere. This can reduce the positive effects compared to oil or, depending on the plant species and location, can even exceed the emissions resulting from oil. The IAASTD calculates that two-thirds of the world’s agricultural land would be required for the cultivation of renewable resources equivalent to just 20% of the global crude oil consumption.

Competition for soil and water

In any event, given the limited availability of water resources and land suitable for cultivation, biofuels directly compete with food cultivation. The production of agrofuels promotes industrial monocultures and enhances their negative impact on rural areas and employment, as well as on the environment. In particular, the IAASTD warns against the expansion of renewable resource cultivation in ecologically valuable natural areas, as this could pose an additional threat to biodiversity. The report is cautious in its assessment of the technical feasibility and efficiency of so-called second-generation biofuels that are produced from algae or the cellulose of trees, shrubs, straw and grass instead of food crops. The problem of competition for increasingly scarce soil and water remains.

Wood biomass

Biofuels are only a small but rapidly growing part of bioenergy production. Worldwide, three billion people use wood for cooking and heating.

Many traditional forms of combustion of wood and charcoal, crop residues and dung are energy inefficient, are harmful to health and climate, and deprive soils of organic matter. In some regions, particularly in Africa, the overuse of firewood is also threatening the already sparse tree populations, while collecting wood consumes working time that could better be invested elsewhere. The IAASTD therefore considers it a crucial task for the future to optimise the traditional use of bioenergy and in particular to develop new energy sources, such as solar cookers for poor rural communities.

Decentralised energy generation

Apart from solar and wind energy plants, local biogas plants for the generation of electricity, as well as small plants for the production of biodiesel, are gaining ground in rural communities worldwide despite some “teething problems”. As long as they are integrated into the local cultivation of food, they should not be lumped together with the large-scale cultivation of energy crops destined solely for huge industrial plants which produce fuels and energy for the world market, thus competing with food production and threatening rural livelihoods.

Facts & Figures

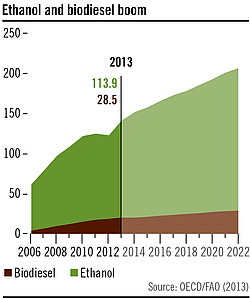

The cultivation of plants for biofuel production is rapidly increasing. The global production of biodiesel for example increased from 7 billion litres in 2006 to an estimated 37.3 billion litres in 2017. Over the same period, ethanol production rose from 55.3 to 123.6 billion litres.

In 2017 the U.S. used 5.4 billion bushels of corn to produce ethanol fuel. The share of corn used for ethanol production rose from 5.9% in the year 2000 to 37.1% in 2017.

Any large-scale change in land use, for biomass for energy, or for sequestration in vegetation, will likely increase the competition for land, water, and other resources, and conflicts may arise with important sustainability objectives such as food security, soil and water conservation, and the protection of terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity.

If Europe’s subsidies were removed from first generation biofuels, the price of food stuffs such as vegetable oil would be 50% lower in Europe by 2020 than at present – and 15% lower elsewhere in the world – according to the EU’s Joint Research Centre.

“Biofuels have direct, fuel‐cycle GHG emissions that are typically 30–90% lower per kilometre travelled than those for gasoline or diesel fuels. However, since for some biofuels, indirect emissions – including from land use change – can lead to greater total emissions than when using petroleum products, policy support needs to be considered on a case by case basis.”

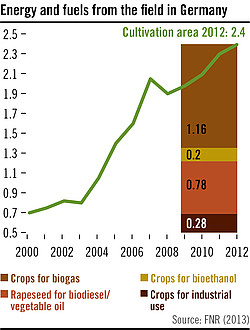

The European land footprint of bioenergy consumption in 2010 was 45 million hectares. By 2030, if current trends continue, EU bioenergy consumption is expected to increase by 58%, occupying 70 million hectares of land – equivalent to the size of Sweden and Poland combined.

Agrofuel production is playing a key role in the purchasing and leasing of large agricultural areas in developing and emerging countries. Around 23% of land deals listed by the Land Matrix are geared towards the cultivation of plants used for the production of agrofuels.

The European Union’s biofuel policy is threatening food security and increasing land grabbing in Africa. 66% of the land that has been grabbed in Africa, some 18.8 million hectares, is intended for biofuel production. Among the largest investors are companies from Europe.

The contribution of biofuel demand to the increase in grain prices from 2000 to 2007 is estimated to be 30 percent. The strongest impact was on maize prices, for which biofuels are estimated to account for 39 percent of price increases.

232 kilograms of corn is needed to produce 50 litres of bioethanol. In Mexico or Zambia, a child could live on that amount of corn for a year.

Around 3 billion people still cook and heat their homes using solid fuels (i.e. wood, crop wastes, charcoal, coal and dung) in open fires and leaky stoves. Most are poor, and live in low- and middle-income countries. Black carbon (sooty particles) and methane emitted by inefficient stove combustion are powerful climate change pollutants.

60% of the primary energy supply in sub-Saharan African comes from biomass, and close to 90% of the population uses biomass for cooking and heating.