The analyses of the IAASTD show the need for an agro-ecological evolution in agriculture, food production and consumption. Since its origins 10,000 years ago, agriculture has always adapted to its respective environmental conditions. It is only in the past 100 years that the development and use of fossil energy sources allowed one part of the world’s population to replace existing practices, which involved careful interaction with nature, with the use of machinery and modern chemicals. Over the past 60 years, this has led to an unprecedented global transformation and exploitation of natural habitats, along with regional agricultural and food systems. Today the consequences of this transformation have become a central problem of humanity.

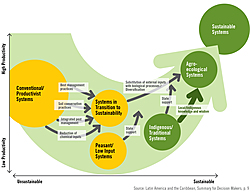

It may seem absurd to millions of farmers in developing countries that agroecology – the adaptation of agriculture to natural conditions and cycles, as well as to local needs – is treated like a new science, a social movement or even as a “romantic niche”. These farmers’ daily bread depends on whether they use the locally available resources optimally to be able to make a living. They measure the efficiency and sustainability of their cultivation systems in terms of the edible yield of their plots of land, as well as the ability to cope with natural disasters and crop failure. Since the 1980s, agroecology as a scientific discipline, practical skill and economic concept for success has received growing support worldwide. The IAASTD attributes a crucial role to agroecology in shaping the future of sustainable agriculture, demonstrating that it has now arrived at the heart of scientific and political debates.

Agroecological approaches

Agro-ecological concepts are primarily based on traditional and local knowledge, and its corresponding cultures. Agroecology combines this knowledge with the findings and methods of modern science. The strength of agroecology lies in the combination of ecological, biological and agricultural sciences, along with medicine, nutritional and social sciences. It incorporates the knowledge of all stakeholders. Their practical contribution to solving complex problems with the help of locally available resources is crucial. Apart from water, soil and sun, other resources that are particularly important are the natural and cultivated diversity of plant species and varieties, along with the knowledge of people and communities on how these plants interact. The IAASTD documents a wealth of both new and old examples of successful agro-ecological adaptation, and describes the enormous potential of agroecology: It can contribute to directly increasing yields, protecting resources, reviving the local economy and improving health, prosperity and resilience.

Agro-ecological farming systems are not good customers for agrochemicals, industrial seeds or heavy agricultural machinery. Moreover, the non-standardized products of agroecological farming are not suited to global commodity markets. As a result, agribusiness shows no interest in the expansion of agroecology. However, at local and international level, a promising market is now developing for goods that are sustainably and fairly produced. These so-called “ethical” and “ethnic” products are high in quality, from a certain region, can be traced back to their origin and have their own story.

Organic farming as a model

Standardized and certified methods, in particular organic farming, are a small but important part of agroecological farming. Organic farming allows for the verification of important criteria such as the non-use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers. This makes it possible to market products internationally as well as develop a global network of producers and consumers for the exchange of information, education and scientific development. However, such attempts to standardize do not capture the diversity of agroecology. It is not a perfect system, nor is it a universal ideology. Agroecology is a continuous, never-ending approximation to the best possible solutions or compromises in the respective local, ecological, cultural and social context.

Agroecology: lots of praise, little support

Agroecological agricultural practices are knowledge-intensive, focus on details and follow a small-scale and long-term approach. This makes them unappealing for public or international large-scale development assistance projects intended to quickly achieve the “best” possible and easily measurable results with as little effort as possible. Shortly after the publication of the IAASTD, when the World Bank received additional billions of funding to be invested in the long-term fight against hunger, the lion’s share of these funds went into large-scale projects, even including subsidies for agrochemicals. Many scientists consider agroecology an unrewarding object of research: It implies too many parameters and levels of consideration, making agro-ecological systems difficult to dismantle and measure. This renders agro-ecological research unsuitable for prompt publications in the journals that are important for fundraising and careers in academia.

For this reason, agroecology has only been systematically promoted in a few countries, such as Brazil, and is often neglected by public funding, despite assertions to the contrary. Non-governmental organizations, communities, local initiatives and farmer organizations, as well as an increasing number of committed consumers, on the other hand, are playing a crucial role in the expansion of agroecology.

The IAASTD contributed substantially to making agroecology a globally recognized concept of ecological, climate-adapted and socially sustainable development. The fact that some try to usurp the concept – albeit with quite different intentions – using terms such as “conservation agriculture” or “sustainable intensification”, is an unmistakable sign of the success of agroecology.

Facts & Figures

96 million hectares worldwide were farmed organically in 2022. Australia has the largest agricultural area farmed organically with 53 million hectares, followed by India (4.7 million ha), Argentina (4 million ha) as well as China and France with 2.9 million ha respectively. The three countries with the largest share of organic farmland are Liechtenstein (43%), Austria (27.5%) and Estonia (23.4%). There were 4.5 million organic farmers in 2022. Around 2.5 million of them live in India, followed by Uganda with 404.246 farmers and Thailand and Ethiopia with around 121.500 farmers.

Agroecology has three facets. It is:

- A scientific discipline involving the holistic study of agro-ecosystems, including human and environmental elements

- A set of principles and practices to enhance the resilience and ecological, socio-economic and cultural sustainability of farming systems

- A movement seeking a new way of considering agriculture and its relationships with society

Agroecology is both a science and a set of practices. It was created by the convergence of two scientific disciplines: agronomy and ecology. As a science, it is the “application of ecological science to the study, design and management of sustainable agroecosystems.” As a set of agricultural practices, agroecology seeks ways to enhance agricultural systems by mimicking natural processes, thus creating beneficial biological interactions and synergies among the components of the ecosystem.

In Cuba, it is estimated that agro-ecological practices are used in 46-72% of peasant farms, generating over 70% of the domestic food production. This equates to 67% of roots and tubers, 94% of small livestock, 73% of rice, 80% of fruits and the majority of honey, beans, cocoa, maize, tobacco, milk and meat production.

A study by Pretty et al., released in 2011, analyzed 40 projects in 20 countries where sustainable intensification has been developed during the 1990s and 2000s. These projects included agroforestry, soil conservation, integrated pest management and horticulture. By early 2010, the projects had benefited 10.39 million farmers and delivered improvements on around 12.75 million hectares. By combining the use of new and improved varieties and new agronomic-agroecological management, crops yields per hectare increased on average by 2.13-fold.

Sales of organic products in the United States rose to $35.1 billion in 2013, up 11.5% from the previous year’s $31.5 billion. It was the fastest growth rate in five years. Fruit and vegetables account for $11.6 billion in sales, up 15% from 2012.

On average, organic farms support 34% more plant, insect and animal species than conventional farms, according to a meta-analysis published in the Journal of Applied Ecology. The researchers looked at data from 94 previous studies covering 184 farm sites dating back to 1989 and found that this effect has remained stable over time.

A meta analysis assessing 114 cases of organic farming in Africa showed that conversion of farms to organic methods increased agricultural productivity by 116%. This figure rose to a 128% increase for projects in East Africa. In Kenya, maize yields increased by 71% and bean yields by 158%.

A report by the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, drawing on an extensive review of the scientific literature published in the last five years, arrived at the following findings: Agroecology raises productivity at field level; agroecology reduces rural poverty; agro-ecological methods contribute to improving nutrition and to adapting to climate change.