The way seeds – the very basis of our food system – are treated globally is a strong reflection of the privatisation of agricultural knowledge. Describing the development of the past hundred years, the IAASTD voices deep concerns regarding the future of our plant genetic resources, their diversity and universal accessibility.

For millennia, farmers have maintained seeds as a common heritage, exchanged them and improved them. At the beginning of the 20th century, seeds were still a public good that scientists improved according to the latest discoveries in genetics, especially Mendel’s laws of inheritance that saw a ‘rediscovery’ at that time. Public institutions systematically categorised seeds and made them available to farmers.

Large international companies dominate the seed market

Based on modern knowledge, the first large public seed collections were established, among others by Nikolai Vavilov in Leningrad. For the first time in the 1930s and 40s, private plant breeders claimed intellectual property rights to newly developed varieties. However, the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), which was agreed in 1961, still ensured that the genetic material remained freely available to everyone for the purpose of breeding other varieties (breeder’s exemption) and that farmers were permitted to re-use the seeds they obtained from their own harvest on their holdings (farmers’ privilege). With the introduction of hybrid seeds in the 1920s through the company Pioneer Hi-Bred the foundation was laid for plant breeding to become a profitable business for private companies. As these high-yielding hybrid varieties do not produce seeds of uniform quality in the next generation, they have the effect of a “biological” plant variety protection.

Since the 1940s, international agricultural research centres have specifically developed new high-breeding varieties, with funding from groups such as the Rockefeller Foundation or the Ford Foundation. These varieties were mainly developed in public non-commercial programmes and made an important contribution to increasing cereal yields and fighting hunger in the 1960s and 70s. However, these high-yielding varieties were accompanied by a rapid global increase in the commercial use of pesticides and fertilisers. In the 1980s, some companies began to systematically invest in genetic engineering. For the first time, exclusive patents on genetic modifications and isolated genetic information made it possible to stop others using certain genetic traits in plant breeding. Since the turn of the millennium, companies have been increasingly successful in even obtaining patents on the results of conventional plant breeding, for example the content of certain substances or in the case of Monsanto’s “severed broccoli” patent, the element of having a long stalk. In addition, plant variety protection was tightened. The UPOV version from 1991 prohibits farmers from exchanging or selling patented seeds and restricts their reuse.

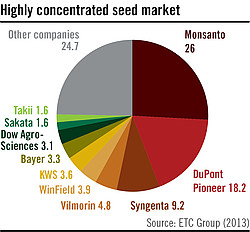

In the 1990s, the seed market became increasingly dominated by a small number of multinational chemical companies, a concentration process that is still ongoing. At the same time, Monsanto, DuPont, Syngenta, Dow, BASF and Bayer control the global pesticide market. In 2008, the IAASTD warned that the top 10 agribusiness companies dominated 50% of the global trade of protected varieties. A few years later, only three companies control 53% of commercial seed sales. These companies focus on just a few profitable plant species, which are cultivated by solvent farmers on a large scale, as well as on regions that offer the necessary infrastructure and legal protection.

The IAASTD questions the benefit of patents and intellectual property rights for innovation, research and the dissemination of knowledge in the seed sector. Over the past years, hopes were smashed that access to patented seeds could be maintained if public universities and research institutes jointly affronted the private sector. Hopes were also dashed that the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) would uphold the fair exchange of genetic resources between private and public plant breeders which is oriented towards the common good.

Patents against diversity and development?

Multinational companies stockpile patents on plants, animals, genetic information and processes, thus making research, development and especially marketing more complicated for their competitors and in publicly funded research. Their exploitation strategy for the new “raw material of knowledge”, including the increasing amounts of accumulated genomic data, mainly consists in barring others from using and further developing this knowledge. The looming threat alone of a long legal dispute of uncertain outcome is often sufficient to hamper further development.

Since the publication of the IAASTD, the global concentration of the seed markets has further advanced. In Africa, many attempts have been made to drastically tighten plant variety protection at regional and national level. Together with the seed industry and private donors, industrialised countries are exerting pressure on African governments to harmonise their seed laws through free trade agreements and development projects. Establishing an economically profitable seed market is one of the central strategies of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), which was initiated by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. In Latin America, one of the fastest growing seed markets, the privatisation process is further increasing, especially in the case of the major cash crops soybeans and maize. In Asia, by contrast, especially in India and China, farmers still have relatively strong rights. In the European Union, as everywhere else in the world, patents on seeds are a bone of contention, reflected in the resistance movements against large seed companies.

Facts & Figures

In 2011, the global commercial seed market was estimated at $34.5 billion. The top 10 companies account for 75% of the global market (up from 67% in 2007). Just three companies – Monsanto, DuPont (Pioneer) and Syngenta – control 53% of the global commercial market for seeds. The world’s largest seed company, Monsanto, now controls 26% of the seed market.

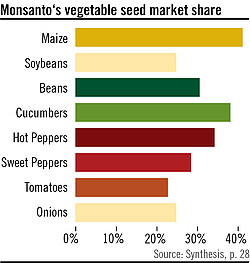

The EU seed markets for economically important crops have undergone an enormous concentration. In the case of maize, just 5 seed companies control 75% of the EU market share. For sugar beet, just 4 companies own 86% of the market. In the vegetable sector, 95% of market share is controlled by the top 5 companies; with agro-chemical company Monsanto already controlling around 24%.

The European Patent Office is granting an increasing number of patents on plants and seeds derived from conventional breeding. Since the 1980s, around 2400 patents on plants and 1400 patents on animals have been granted in Europe. The EPO has granted more than 120 patents on conventional breeding and about 1000 such patent applications are pending. The scope of many of these patents often covers the whole food chain from production to consumption.

In June 2013, Seminis, a company owned by Monsanto, was granted patent EP 1597965 on broccoli. The patent claims plants derived from conventional breeding grown in such a way as to make mechanical harvesting easier. The patent covers the plants, the seeds and the “severed broccoli head”. It additionally covers a “plurality of broccoli plants … grown in a field of broccoli.” The method used to produce these plants was purely crossing and selection.

Monsanto has a history of suing farmers and investigating those who are not contractual partners, but whose fields are contaminated by GM pollen, or the seeds from neighbouring fields. As of November 28, 2012, Monsanto had filed 142 lawsuits against farmers for alleged violations of its Technology Agreement or its patents on GM seeds. Monsanto won 72 lawsuits and was awarded a total sum of $23.7 million.

Intellectual property rights will lead to transfers of resources from technology users to technology producers. The oligopolistic structure of the input providers’ market may result in poor farmers being deprived of access to seeds’ productive resources essential for their livelihoods, potentially raising the price of food, making food less affordable for the poorest.

Globally, there are approximately 382,000 species of vascular plants, out of which a little over 6,000 have been cultivated for food. Of these, fewer than 200 species have significant production levels globally, with only nine (sugar cane, maize, rice, wheat, potatoes, soybeans, oil-palm fruit, sugar beet and cassava) accounting for over 66% of all crop production by weight.