The misery of millions of small-scale farmers is often the result of unfair competition between large, world market-oriented agricultural companies and small family farms. Millions of smallholders worldwide produce just enough for their families to survive. However, smallholders are often unable to produce enough and suffer from hunger. Only small-scale farmers who are able to sell their products at an adequate price will produce more than their families consume, and only under these circumstances can these farmers contribute to feeding other people and make provisions for hard times. The first precondition for this is access to markets. The second requirement is the possibility to invest and handle the risks associated with the investment. Millions of farmers, especially women, fail to comply with these basic prerequisites. Local, regional and national markets remain closed to them. The necessary infrastructure, incentives, information, protection from competition and systematic development are all missing. It is often easier for cheap finished products from industrialised countries to gain access to the markets in the cities of the Global South than it is for products from the region itself.

Unequal partners

The international terms of trade – the conditions of global agricultural trade – emerged in the colonial era of the 19th century. Today they are regulated by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and a large number of bilateral and multilateral trade agreements. Their declared objective is to expand and liberalise international trade through the elimination of tariffs and trade restrictions. In theory, free markets and worldwide competition reduce the global costs of production, thus increasing prosperity. However, it is frequently doubted that this can hold true for agricultural production and, at the same time, for the management of our limited natural resources, as long as the local ecological and social conditions differ completely.

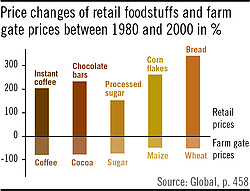

Development of producer and retail prices

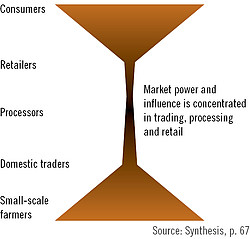

It is undisputed that the current conditions prevailing on the world market for agricultural commodities do not provide basic food for everyone through sustainable production. According to the IAASTD, the conditions of global agricultural trade would have to be radically changed in order to achieve this aim. Producer prices for agricultural commodities fell steadily since the Second World War and continued to do so roughly until the turn of the millennium. Correspondingly, the income of the majority of farmers worldwide has also decreased. In industrialised nations, the number of farmers declined, while average farm size increased. At the same time, the operating costs for farm machinery, pesticides, energy, seeds and other inputs increased in the course of the industrialisation of agriculture. Farmers’ share in retail prices, however, has decreased dramatically for the benefit of retailers and food processors.

Within all upstream and downstream industries to agriculture, an increasing global and national concentration is taking place in the hands of just a few companies, which dominate the market. This is exacerbated by a growing vertical integration along the value chains – chemical companies are controlling the global seed market; raw material traders are controlling transport routes, mills and refineries; supermarket chains are dominating wholesale trade; and processors are controlling their contract farmers. This process is reinforcing the economic marginalisation of small-scale and subsistence farmers which are of no interest to the global industry, neither as customers nor as suppliers. Even though the percentage of agricultural production, which is traded internationally, is relatively small (around 14% in the case of cereal production), world market prices have an enormous leverage effect. They also determine domestic prices, particularly in smaller countries with unprotected markets. If local producers charge higher prices, they are immediately pushed out of urban markets.

Agricultural exports hinder the development of domestic markets

World trade has an enormous impact on agricultural policies in many developing countries.

Rather than providing the population with food, or promoting the development of domestic markets and rural areas, governments and local elites frequently pursue the primary goal of generating foreign currency and tax revenue from agricultural exports. Although large parts of their populations are suffering from hunger, especially in rural areas, many countries still choose to supply cheap raw materials for the animal feed, fibre, (bio)fuel and luxury food industries in the North, with devastating ecological and social costs. As net-importers of food, these countries become dependent on world markets over which they have no influence. The IAASTD identifies the least developed countries and the poor in rural areas as the losers of global trade and its ongoing liberalisation.

The report warns against an opening of markets if cheap imports and exports hinder rural and agricultural development, and threaten food security and incomes of the population. The IAASTD also points to the fact that import tariffs make up one quarter of state revenues in some poor countries and are relatively easy and reliable to collect. The loss of these revenues could therefore reduce the potential of public social and structural policies, and the already weak capacity of public institutions to act. Industrialised nations themselves frequently make use of tariff escalation for imported goods, with import tariffs increasingly depending on the degree of processing that has occurred. This allows industrialised countries, in which agriculture is rarely an important economic sector, to import cheap raw materials, while setting higher tariffs for processed goods to protect their own processors. This prevents many countries in the South from developing their own processing industries and creating jobs.

Fair prices for sustainable production

The IAASTD calls for a radical change of direction in current policies: Farmers, particularly those in developing countries, must be paid an adequate price for their environmental services they provide during production (such as soil and biodiversity conservation, water management and the reduction of carbon emissions). This could include climate or environmental charges, whose collection is organised by states and that are distributed purposefully and fairly from a global perspective. The IAASTD describes the EU subsidies for agri-environmental measures as a step into the right direction. In developing countries, such programmes could boost rural development and ensure that ecological sustainability can be financed. Private sector approaches could also make an important contribution.

Fair trade initiatives and trade with organic products allow consumers in cities, both in the North and the South, to actively support sustainable forms of agriculture through informed purchasing decisions. These private sector initiatives, which were introduced as an alternative to the mainstream commodity market, have proved to be an effective way to reduce poverty. Apart from this direct economic effect, these decisions only to buy products, of which their producers can also make a living, can exert a healthy dose of pressure on the rest of the market.

Facts & Figures

With agri-food exports reaching €122 billion in 2014, the EU became the world’s number one exporter of agricultural and food products, followed by the US with €121 billion worth of exports. Final products for direct consumption made up most of the EU’s exports. The top ranking product in EU agri-food imports in 2014 was tropical fruit, with imports worth €10.3 billion. Other popular imported products were oilcakes from soybeans (€8.7 billion), soybeans (€5.1 billion) and palm oil (€5.6 billion).

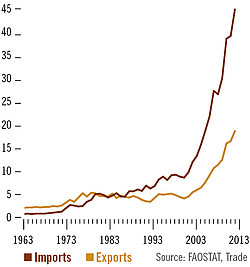

Africa has turned from a net exporter of agricultural products to a net food importer. In 1980, agricultural trade was balanced with both exports and imports at about $14 billion. In 2007, imports reached a record high of $47 billion, yielding a deficit of around $22 billion. By 2023, Africa’s trade deficit in volume terms will increase to 44 million tonnes for wheat and 18 million tonnes for rice. Asia is expected to exhibit a trade deficit for all commodities except rice, vegetable oils and fish.

In 2009, out of 153 developing countries, 92 depended on commodities for at least 60% of their export earnings. Dependency was particularly high in Western and Central Africa, where commodities made up 95% of exports. Commodity dependence in developing regions rose 20% between 1999-2001 and 2009-2011.

“On average, 15% of EU farms sell more than half of their production directly to consumers. This enables them to retain a greater share of the products’ market value, through the elimination of intermediaries, which can potentially increase their income.”

The world’s ten largest food and beverage companies (Associated British Foods, Coca-Cola, Danone, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Mars, Mondelez, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever) collectively generate revenues of more than $1.1 billion a day. However, none of these companies has committed to paying a fair price to farmers, nor are they committed to fair business arrangements with farmers.

With combined sales reaching $753 billion, the top ten retail food companies accounted for around 10.5% of all groceries bought worldwide in 2009. The top three supermarket retailers (Walmart, Carrefour and Schwarz Group) control 48% of the revenues earned by these top ten retail food companies. With combined sales of $387.5 billion in 2009, the ten biggest food and beverage processing firms controlled an estimated 28% of the global market for packaged food products.

Subsidised EU milk causes unfair competition to poor farmers in Bangladesh according to a recently released ActionAid report. An example of this advantage can be seen in the way that the European dairy giant Arla Foods profits from EU-subsidised milk powder sales to Bangladesh, giving it a huge advantage over local producers. In 2010, the EU exported 378,000 tonnes of skimmed milk powder to developing countries, mainly in Africa and the Middle East.