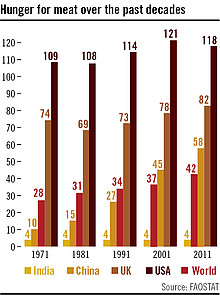

Over the past 55 years, global meat production has almost quadrupled from 84 million tons in 1965 to 340 million tons in 2020. The IAASTD predicts that this trend will continue, especially because the growing urban middle classes in China and other emerging economies will adapt to the so-called western diet of people in North America and Europe with its taste for burgers and steaks.

On average, every person on Earth currently consumes around 45 kilograms of meat per year. This figure includes babies and adults, meat eaters and vegetarians alike. In 2013, US citizens consumed 115 kilograms of meat and people in the UK 81 kilograms, while citizens in India only ate 3.7 kilos. In general, men eat more meat than women. In the EU, meat consumption has stagnated recently, with a growing number of people switching to vegetarian and vegan diets. Moreover, beef has lost in popularity while the consumption of chicken has increased remarkably. The favourite meat of Europeans is pork. The Chinese also share this appetite for pork. Since 1965, per capita meat consumption in China has increased six-fold. Since the population almost doubled to 1.4 billion people over the same period, global demand for meat and animal feed has exploded.

Plate or feed trough?

The production of meat, milk and eggs leads to an enormous loss of calories grown in fields, since cereals and oil seeds have to be cultivated to feed to animals. According to calculations of the United Nations Environment Programme, the calories that are lost by feeding cereals to animals, instead of using them directly as human food, could theoretically feed an extra 3.5 billion people. Feed conversion rates from plant-based calories into animal-based calories vary; in the ideal case it takes two kilograms of grain to produce one kilo of chicken, four kilos for one kilogram of pork and seven kilos for one kilogram of beef.

By their nature, cattle and sheep eat grass. More than two thirds of the global agricultural area is used for permanent meadows and pastures. If livestock eat grass and other plants that are not suitable for direct human consumption, they do not compete for cereals but increase food supply and add significantly to agricultural production. They produce manure, contribute to soil cultivation, serve as draught and pack animals, recycle waste and stabilise the food security of their owners.

Large parts of the grasslands used today, especially in arid regions, are not suitable for any other agricultural use except extensive grassland management. However, it is no longer possible to substantially increase its production capacity. In some areas of the world, overexploitation of grasslands, also through traditional livestock husbandry, has become a serious problem. In addition, chickens, pigs and other small animals, which are traditionally kept to make use of waste and other by-products, eat worms or acorns, can complement food production and optimise the use of resources.

Today, however, most fattened livestock no longer eat grass and are kept in increasingly bigger factory farms and are fed with concentrated feedstuff based on soybean, rapeseed, maize, wheat or other grains instead. Grown on arable land, the production of animal feed thus results in land for direct food production being lost. This is increasingly becoming a problem if the competition for food is “outsourced” to other countries or regions. The EU, for example, imports more than 70% of protein crops for its animal feed, mostly soybean and soy meal from Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and the United States. The area used in these countries for the production of such export crops is equivalent to 20% of the entire surface of arable land in the EU. Rainforests are cut down and large pasture areas are converted into cropland for the cultivation of soy. Not only is this a catastrophe for global biodiversity and climate protection, it also negatively impacts soil fertility due to large monocultures.

In Europe, the cultivation of soy and other domestic protein crops such as broad beans, field peas and lupines, has not been competitive for decades even though the cultivation of leguminous plants has many advantages. Legumes can fix nitrogen from the air in symbiosis with bacteria at their roots, thus replacing mineral fertilisers or animal manure. Leguminous plants could make an essential contribution to climate protection and soil fertility. On that issue, there is agreement between the EU agricultural ministers and the European Parliament. However, during the last reform of the Common Agricultural Policy, they did not manage to establish the cultivation of leguminous plants as a mandatory part of the minimum crop rotation. In the framework of the so-called greening, they gave farmers the possibility to cultivate leguminous plants on 5% of their fields, thus enabling them to fulfil their “Ecological Focus Area” requirement, which would actually be obligatory.

Climate killer number one

The industrial production of meat, milk and eggs, which is no longer tied to pastures, first requires the cultivation of many times the amount of calories in the form of cereals and oil seeds. These crops are mainly cultivated in highly energy-intensive monocultures. In addition, ruminants emit the dangerous greenhouse gas methane and livestock causes ammonia emissions from manure and dung. The livestock sector is therefore responsible for by far the biggest contribution of agriculture to climate change. The extremely negative impact of meat and dairy production on the climate could partly be mitigated by improving the composition of animal feed in order to reduce methane emissions. Additional sources of feed, for example from organic waste and unused bycatch in fishery, could also enhance efficiency in this area. Furthermore, a better distribution of meat production facilities is necessary in order to reduce transport distances and allow for the use of animal dung in those places where nutrients were removed from the soil.

Need for change in consumer habits

Although the IAASTD does not give recommendations with regard to consumer habits, the results of the report only allow for one conclusion: The consumption of meat and dairy products in industrialised countries has to be reduced and consumption in emerging countries has to be limited to an acceptable level. These are the most urgent and most effective steps that must be taken to achieve food security and to protect natural resources and the climate. Considering the disastrous consequences of meat consumption, would it really be so radical to follow our grandparents’ tradition of a Sunday roast rather than eating meat every day? Not only would this be good for our health but also for food safety and the environment. The respectful treatment of farm animals would be beneficial to their well-being as well as to our self-respect. When buying meat at the supermarket, we would no longer have to suppress images of unbearable conditions in modern meat factories; of the destruction of forests, animal and plant varieties; or of global warming – all of which are consequences of this form of production – together with the decay of rural areas and farmers’ livelihoods.

Facts & Figures

In 2021, around 355.7 million tons of meat were produced worldwide. For 2022, the FAO forecasts an increase to 360 million tons. If a global average is taken, meat consumption amounted to 44.7 kilograms of meat per person in 2021.

Between 2000 and 2014, the global production of meat rose by 39% and milk production increased by 38%. The FAO estimates that by 2030, meat production will increase another 19% compared to the period 2015-2017, with developing countries accounting for almost all of the total increase. Milk production is projected to grow by 33% in the same period.

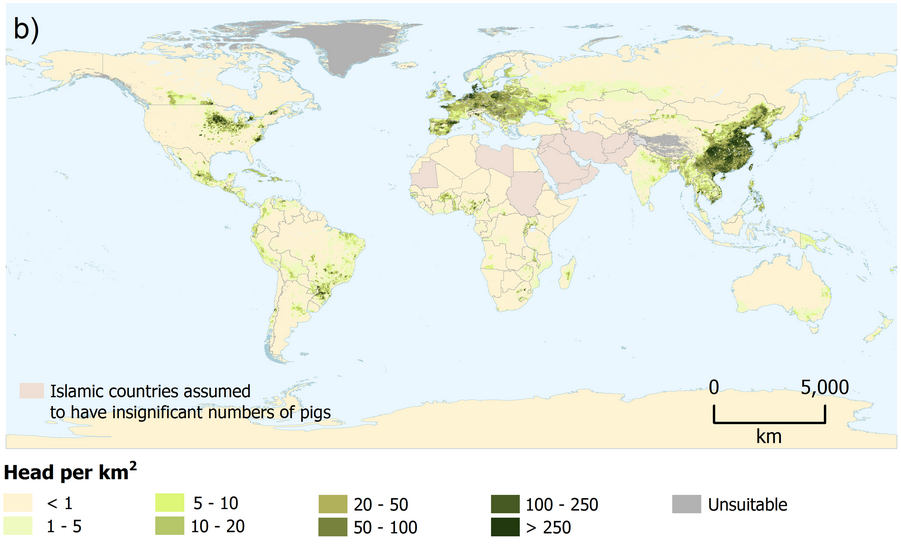

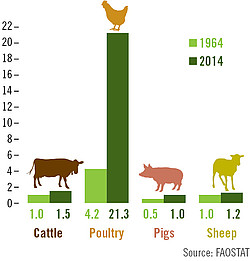

There are billions of farm animals worldwide. In 2016, the cattle population reached 1,474 million animals, up 44% from 1966. The number of chickens grown for human consumption increased from 4.4 billion to 22.7 billion between 1966 and 2016. During the same period, the pig population grew by 92% to reach 981 million heads.

One in eight Brits – or almost 13% of the population – is now vegetarian or vegan, with a further 21% identifying as ‘flexitarian’, according to new research by supermarket chain Waitrose. This means that a third now has meat-free or meat-reduced diets. 60% of vegans and 40% of vegetarians have adopted the lifestyle over the past five years, mostly due to animal welfare and health concerns.

Livestock is the world’s largest user of land resources, with pasture and arable land dedicated to the production of feed representing almost 80% of the total agricultural land. One-third of global arable land is used to grow feed, while 26% of the Earth’s ice-free terrestrial surface is used for grazing.

Greenhouse gas emissions associated with livestock supply chains add up to 7.1 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-eq) per year – or 14.5% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Emissions are caused by feed production, enteric fermentation, animal waste and land use change. Cattle (beef, milk) are responsible for about two-thirds of that total, largely due to methane emissions.

Research shows that the five largest meat and dairy corporations combined (JBS, Tyson, Cargill, Dairy Farmers of America and Fonterra) are responsible for annual greenhouse gas emissions of an estimated 578.3 Mt – more than major oil companies such as ExxonMobil (577 Mt), Shell (508 Mt) or BP (448 Mt). The combined emissions of the top 20 meat and dairy companies (933 Mt) even surpass the emissions from entire nations, such as Germany (902 Mt), Canada (722 Mt) or the UK (507 Mt).

Nearly 60% of the world’s agricultural land is used for beef production, yet beef accounts for less than 2% of the calories that are consumed throughout the world. Beef makes up 24% of the world’s meat consumption, yet requires 30 million square kilometres of land to produce. In contrast, poultry accounts for 34% of global meat consumption and pork accounts for 40%. Poultry and pork production each use less than two million square kilometres of land.

A 2,000 kcal high meat diet produces 2.5 times as many greenhouse gas emissions as a vegan diet, and twice as many as a vegetarian diet. Moving from a high meat to a low meat diet would reduce a person’s carbon footprint by 920kg CO2e every year – equivalent to a return flight from London to New York. Moving from a high meat diet to a vegetarian diet would save 1,230kg CO2e per year.

The production of one kilogram of beef requires 15,414 litres of water on average. The water footprint of meat from sheep and goat (8,763 litres) is larger than that of pork (5,988 litres) or chicken (4,325 litres). The production of one kilogram of vegetables, on the contrary, requires 322 litres of water.