Water is getting scarce – but what does this actually mean? After all, the planet never loses a single drop of H2O. Although water is a finite resource, it will not be used up as long as we do not render it permanently unusable. However, it is important to integrate human water usage into the natural hydrological cycle and to use the locally available water in an adequate, effective, sustainable and fair way. Despite significant progress in this area, there are still millions of people who do not have access to safe drinking water. Everyday, millions of women and children have to walk long, and often dangerous, distances in order to collect water and carry it home. As is the case for food and land, access to clean drinking water and water for agricultural usage is unequally distributed.

Green and blue water

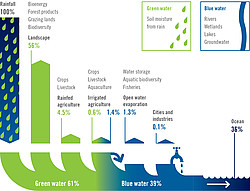

When it comes to freshwater most people think of water in rivers and lakes, groundwater and glaciers, the so-called “blue water”. Only part of the rainfall feeds this freshwater supply. The majority of rainfall comes down on the Earth’s surface and either evaporates directly as “non-beneficial evaporation” or, after being used by plants, as “productive transpiration”. This second type of rainwater is termed “green water”. The green water proportion of the total available freshwater supply varies between 55% and 80%, depending on the region of the world, as well as local wood density. The biggest opportunity and challenge for future water management is to store more green water in soil and plants, as well as storing it as blue water.

Competition for a scarce resource

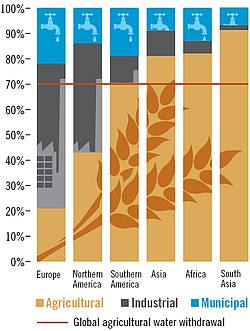

Agriculture is by far the largest consumer of the Earth’s available freshwater: 70% of “blue water” withdrawals from watercourses and groundwater are for agricultural usage, three times more than 50 years ago. By 2050, the global water demand of agriculture is estimated to increase by a further 19% due to irrigational needs. Approximately 40% of the world’s food is currently cultivated in artificially irrigated areas. Especially in the densely populated regions of South East Asia, the main factor for increasing yields were huge investments in additional irrigation systems between the 1960s and 1980s. It is disputed where the further expansion of irrigation, as well as additional water withdrawals from rivers and groundwater, will be possible in the future, how this can take place and whether it makes sense. Agriculture already competes with peoples’ everyday use and environmental needs, particularly in the areas where irrigation is essential, thus threatening to literally dry up ecosystems. In addition, in the coming years, climate change will bring about enormous and partly unpredictable changes in the availability of water.

In some regions of the world, water scarcity has already become an acute problem. The situation will deteriorate dramatically in the decades to come if we continue to overuse, waste and contaminate the resources available at local and regional levels. The IAASTD warns against bitter disputes within societies, but also between states, right up to violent conflicts and wars over water. Agriculture could reduce water problems by avoiding the cultivation of water-intensive crops such as maize and cotton in areas which are too dry for them, as well as by improving inefficient cultivation and irrigation systems that also cause soil salinisation. Other practices that could be avoided include the clearance of water-storing forests, evaporation over land left lying fallow and the (in some parts of the world) dramatic overuse of groundwater sources.

Pollution, contamination and over-fertilisation

The pollution and contamination of entire watercourses is another grave problem. Water carries many substances: fertile soil that has been washed out, as well as nutrients which in high concentrations over-fertilise watercourses and deprive them of oxygen. Water can also contain pesticides, salts, heavy metals and sewage from households, as well as an enormous variety of chemical substances from factories. While many rivers and lakes in Europe are slowly recovering from direct pollution through industrial discharges, the problem is massively increasing in densely populated regions of Asia and other emerging economies. The use of water further downstream is becoming increasingly risky and expensive, sometimes impossible. Toxic substances in the groundwater can make this treasure unusable for entire generations. Agriculture is polluting water bodies with pesticides and huge amounts of nitrogen. The number and size of so-called “dead zones” in estuarial areas of large streams, where marine life is suffocating due to over-fertilisation, are expanding.

Responsible use and common distribution

The IAASTD recommends irrigating agricultural areas more efficiently than today and intensifying the “water harvesting” of precipitation. The report describes easy methods to avoid water evaporation directly from the soil, to increase the water storage capacity of soil and vegetation, and to build local water reservoirs and irrigation systems. According to the IAASTD, in the world’s most vulnerable regions there is hardly any other measure as effective for the stabilisation of the hydrological cycle as the conservation and expansion of forests and trees.

Decisive for the sustainable use of our water resources are water management systems which take all users of a watershed into account and provide them with the necessary rights and duties to maintain this common property. The IAASTD does not rule out that the water-scarce regions of Africa and Central Asia will have to import food products from regions with abundant water resources in the future. Today, this export of “virtual water” already takes place on a large scale, although in the opposite direction. Water embedded in cash crops is imported from developing countries, flowing mainly as animal feed into the meat production systems of industrialised countries.

Facts & Figures

Some 3 in 10 people worldwide, or 2.1 billion, do not have access to safe, readily available water at home, with 844 million of them lacking even a basic drinking water service. 159 million people still drink untreated water from surface water sources, such as streams or lakes, 58% them living in sub-Saharan Africa. 4.5 billion people still lack safely managed sanitation services. This includes 892 million people – mostly in rural areas – who defecate in the open.

Contaminated water can transmit diseases such diarrhoea, cholera, dysentery, typhoid and polio. Contaminated drinking water is estimated to cause more than 502,000 diarrhoeal deaths each year.

A combination of rising global population, economic growth and climate change means that by 2050 five billion (52%) of the world’s projected 9.7 billion people will live in areas where fresh water supply is under pressure. Researchers expect about 1 billion more people to be living in areas where water demand exceeds surface-water supply.

69% of the world’s freshwater withdrawals are committed to agriculture. The industrial sector accounts for 19% while only 12% of water withdrawals are destined for households and municipal use.

Future global agricultural water consumption (including both rainfed and irrigated agriculture) is estimated to increase by about 19% to 8,515 km3 per year by 2050.

Every day for more than 20 years, an average of 2,000 hectares of irrigated land in arid and semi-arid areas across 75 countries have been degraded by salt. Today about 62 million hectares are affected – 20% of the world’s irrigated lands. This is up from 45 million hectares in the early 1990s.

Anthropogenic inputs of excess nutrients into the coastal environment, from agricultural activities and wastewater, have dramatically increased the occurrence of coastal eutrophication and hypoxia. Worldwide there are now more than 500 “dead zones” covering 250,000 km2, with the number doubling every ten years since the 1960s.

Agriculture is a significant water user in Europe, accounting for around 33% of total water use. This share varies markedly, however, and can reach up to 80% in parts of southern Europe, where irrigation of crops accounts for virtually all agricultural water use.

According to the OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050, global water demand will increase by 55% due to growing demand from manufacturing (+400%), thermal power plants (+140%) and domestic use (+130%). These competing demands will put water use by farmers at risk. 2.3 billion more people than today – 40% of the global population – will be living in river basins under severe water stress.

Irrigation provides approximately 40% of the world’s food, from an estimated 20% of agricultural land, or about 300 million hectares globally. Almost half of the total area being irrigated worldwide is located in Pakistan, China and India, and covers 80%, 35% and 34% of the cultivated area respectively.