According to estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organisation, up to 757 million people, almost one in eleven, are currently undernourished, regularly not getting enough food in order to lead an active and healthy life. At the same time, agriculture is producing more food than ever before, both in total numbers as well as on a per capita basis, despite the fact that the world population is growing. If the harvest was used entirely and as effectively as possible as food, it could already feed 12-14 billion people.

The changeable history of the fight against hunger is as old as humanity whose populations had to adapt again and again to changing environmental conditions, epidemics and other adversities. For the first time since the beginnings of agriculture, humanity now has the means at its disposal to overcome world hunger.

At the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome, heads of state and government solemnly vowed to halve the number of people suffering from hunger to 425 million by 2015. The United Nations had already declared food an inalienable human right in 1948. However, today, people affected by hunger still do not have effective means of enforcing their right to adequate food and freedom from hunger. If they really wanted to, all governments worldwide could ensure that their citizens have enough to eat. A few countries would have to accept temporary foreign aid for this purpose. India, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia, however, where more than half of the world’s hungry live, do certainly not belong to these countries.

Global hunger statistics: flexible curves and goals

The global number of undernourished people published by FAO each year refers to a 3-year average and is based on complex assumptions and calculations, as well as national statistics of different quality and independence. Many of these assumptions have proved to be highly flexible. In 2009, the FAO warned that more than a billion people were suffering from hunger; in 2010 the number was 925 million. In 2011, the FAO revised its methodology. The number of undernourished then dropped to 868 million people, reaching 795 million in 2015. The goal of the 1996 World Food Summit of halving, between 1990 and 2015, the absolute number of people who suffer from hunger remained unattainable, whereas the Millennium Development Goal was narrowly missed. It was cunningly adapted only to halve, within the same period, the proportion of undernourished people, while the world population has grown by 2 billion people since 1990. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 now aims at ending all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030.

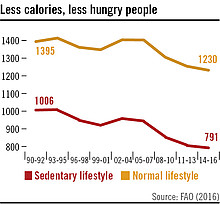

The updated FAO method now captures food losses but also assumes that people, on global average, are less physically active and somewhat smaller, and that distribution inequalities are less marked than previously thought. These and other assumptions changed, as if by magic, the curves depicting the number of hungry people, which no longer tended upwards but downwards. The most important basis for the calculation of the number of undernourished is the daily energy requirement of a person. The FAO assumes a “sedentary lifestyle”, which is common in the case of office work. On global average, the minimum dietary energy requirement (MDER) for this lifestyle is 1844 kilocalories per day. If the calculations were based on a “normal lifestyle” – and in this case a minimum of 2023 kilocalories – the number of undernourished would have zealed from 842 to 1297 billion people, or from 805 to 1210 billion if the FAO estimates for the period 2012-2014 are considered.

Victims of natural disasters such as drought and floods, or of conflict and civil war, make up the minority of people affected by hunger. The picture of hunger and misery painted by the media does not show the silent majority of those unable to lead a normal life due to a chronic lack of food. Undernourishment makes them too weak to learn and work normally, causes irreparable damages and makes those affected susceptible to infectious diseases and parasites.

Mothers and children in their first years of life are hit hardest by malnutrition. The 1000 days between a woman’s pregnancy and her child’s second birthday are considered critical to the physical growth and brain development of a child. Every year, almost seven million children under five die; one third of them due to pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria. UNICEF estimates that nearly half of them could survive with better nutrition. The number of children with stunted growth is even higher than that of underweight children. Stunting causes irreversible cognitive and physical damage, perpetuating the cycle of hunger and poverty in the next generation.

Hunger can only be overcome locally

More than 70% of the hungry live in rural areas. They are small-scale and subsistence farmers, pastoralists, fishermen, rural workers and landless people who directly depend on local land and water use. These rural poor frequently do not have secure access to sufficient amounts of food. Access to land, water and means of production, as well as training, know-how and a minimum of social protection in emergency situations determine in the first place whether or not their human right to sufficient and nutritious food is fulfilled. In second place, additional employment opportunities in rural areas are needed. Therefore, a central message of the IAASTD report is that hunger is primarily a rural problem that can only be overcome locally in the long term. Accordingly, regional self-sufficiency with food is, wherever possible, the essential backbone of sustainable rural development.

Misery and rural exodus

Over the past few decades, the situation of the rural poor in many regions of the world has deteriorated dramatically. Small-scale farmers have been displaced, their income has steadily decreased and their yields have stagnated. Especially in Africa, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has left millions of families and communities without their most active members and the burden of additional costs and extra work in order to care for the sick and orphaned. It is mostly young men who look for work in the cities, leaving women, children and the elderly behind, often in precarious situations. Rather than building up reserves for crises or crop failures, or producing surpluses they could sell to obtain money for necessary investments, they only manage to grow food for their survival.

Rural exodus is shifting hunger and poverty to the slums and suburbs of the growing mega-cities, where money is an even more decisive factor than in rural areas. For poor people who spend much of their income on food, already modest increases in food prices will have a dramatic effect. An explosion of food prices such as in the years 2008 and 2011 therefore caused thousands of people whose livelihoods were threatened to take the streets. Their hunger revolts, mainly in the capitals, contributed to the fact that governments in Asia and Africa today take self- sufficiency in food more seriously than at the time the IAASTD was adopted (see also food sovereignty).

A question of political will

In many of the hardest hit countries, weak governments at national and regional level frequently have other priorities than fighting hunger in the population. Humanitarian and development aid can even become an important source of income for those in power, who use the misery of their own people to their own advantage. The failure of many governments in the fight against hunger is often caused by corruption, incompetence, war and internal conflict. The arrogance and ignorance that urban elites display with respect to rural development present further problems. The erosion and collapse of state rule, especially in remote rural regions, often leads to local violence and exploitative structures in which little value is given to human life.

Facts & Figures

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the estimated total number of undernourished people in the world reached between 713 and 757 million people in 2022. Considering the middle of the projected range (7353 million), 152 million more people were facing hunger in 2023 than in 2019. The vast majority of hungry people live in developing regions.

52.4% of the world’s hungry or 384.5 million people live in Asia, followed by Africa, home to 40.7% (298.4 million people) of the world’s undernourished population, and Latin America and the Caribbean (5.6% or 41 million people). The highest prevalence of undernourishment was found in Africa, where 20.4% of the total population was undernourished. In Middle Africa and Eastern Africa, the figures were even at 30.8% and 28.6% respectively.

According to the 2024 Global Hunger Index (GHI), hunger remains serious or alarming in 42 countries, especially in Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia. 6 countries have alarming levels of hunger: Burundi, Chad, Madagascar, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen. The index combines four indicators (undernourishment, child wasting and stunting and child mortality). In 22 countries with moderate, serious, or alarming GHI scores, hunger has actually increased since 2016 and in 20 countries, it has declined by less than 5% from the 2016 GHI scores. If current trends observed since 2016 continue, the world will not reach even low hunger until 2160 – more than 130 years from now.

In 2021, close to 193 million people were acutely food insecure and in need of urgent assistance across 53 countries/territories, according to the GRFC 2022. This represents an increase of nearly 40 million people compared to the previous high reached in 2020. Of these, over half a million people (570,000) in Ethiopia, southern Madagascar, South Sudan and Yemen were classified in the most severe phase of acute food insecurity and required urgent action to avert widespread collapse of livelihoods, starvation and death.

In 2020, 149.2 million children worldwide – or almost one in five children (22%) – were stunted due to chronic malnutrition. Asia and Africa accounted for 53% and 41% of all stunted children respectively. An estimated 45.4 million children under the age of five suffered from wasting due to acute malnutrition. 70% of all children affected by wasting live in Asia and more than half of all children affected by wasting live in Southern Asia.

In 2020 alone, 5.0 million children worldwide died before reaching their fifth birthday. On average, around 13,700 children died every single day and almost ten children every minute. Communicable and infectious diseases continue to be leading causes of under-five deaths. Nutrition-related factors contribute to about 45% of deaths in children under the age of five.

In 2021, 13.5 million US households (or 10.2%) were “food insecure”. That means that at times during the year, these households were uncertain of having or unable to acquire enough food to meet the needs of all their members due to a lack of resources. Around 5.1 million households or 3.8% had “very low food security”. In those homes, the food intake of some household members was reduced and normal eating patterns were disrupted at times during the year due to limited resources.

Agriculture produces a third more calories than are needed to feed the entire world population. Per capita food availability rose from about 2,716 calories per person per day at the turn of the millennium to 2,908 calories in 2016-2018. Even the least developed countries recorded an increase from 2,083 calories per person per day to 2,336 in the same period.

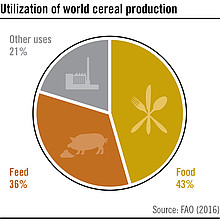

In 2023, world cereal production reached a record output of 2.84 billion tonnes, up almost 22% from 2.3 billion in 2011. Despite this record-breaking harvest, of the 2.83 billion tonnes of cereals that were utilzed only 42.3% were used to feed people, 37.5% was used for animal feed and the remainder for other uses such as seed, industrial non-food and waste.

The FAO Food Price Index reached a record high of 159.7 points in March 2022, up 13% from February when it had already reached its highest level since its inception in 1990. The Index tracks monthly changes in the international prices of a basket of commonly-traded food commodities. The March level of the index was 34% higher than in the same month of 2021. The war in Ukraine drove the large increases in international prices for wheat, maize and vegetable oils.